The dumpster fire has become this year’s meme du jour, and for good reason. It’s been, to put it mildly, a really crappy year. In addition to all the global reasons for this relentlessly depressing crapshoot of a year, I have my own reasons for needing 2016 to just be over already. On November 5, while I was on a plane to my home town in South Africa, my dad passed away after a 20-year battle with cancer.

I’m going to back up a little.

Going home

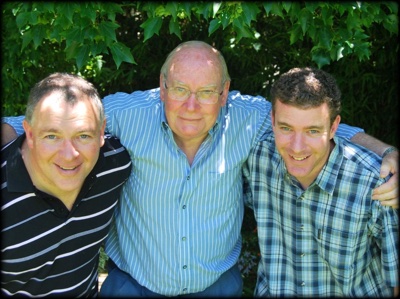

I traveled to South Africa three times this year. After a decades-long remission, my dad’s prostate cancer came back with a vengeance towards the end of 2015. At that point I don’t think any of us thought that he would actually not be alive at Christmas 2016. But still, I went back in January to spend time with him while he was still mostly feeling ok.

I went back again in July. Things started progressing (regressing?) much faster than we expected, and the reality started to set in. For the first time, we realized that it’s time to face facts: our ever-present rock and safe haven is starting to lose his battle. So I spent almost 3 weeks there. Dad was mostly in bed, but we did manage to take him out a few times. It was good. We decided, very rationally, that I wouldn’t come back for the funeral. That funerals are for other people, and this visit was for Dad. So we’ll be ok.

Oh, how silly of us to think that.

Moment of change

By the middle of October it became clear that Dad only had a few weeks left to live. As Mike Tyson once said, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” The news was a giant punch in the mouth and I realized our previous plan was stupid. I had to go. I had to be there. I booked a ticket.

At that point we had no expectation that I would make it in time. But as it came closer, and Dad hung on, I started to hope. When I went to the airport on November 3rd he was still hanging on, and we all started to think I might actually make it. But then there was a flight delay. And not just any delay. A delay that meant I had to go home and come back for the next day’s flight.

I was in the air, on my way to Amsterdam, when my brother’s message came through.

Dad passed away at 3:15am SAST.

I stared at it. I didn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it. How could this be. I’m in an airplane. Dad is invincible. This isn’t right. This isn’t how it works.

The rest of the week… The only words I have to describe that week is that it felt surreal and banal. I spent my birthday at the funeral home, picking out a casket. We spent time in coffee shops organizing the obituary and planning food for the funeral.

What the hell?

The lesson

I did learn two very important things that week, though. The first is that the death of a parent is way more difficult than it might seem. I always thought that even though sad, the death of a parent wouldn’t be something that paralyzes me completely. It’s somewhat expected, and you have your own family to fall back on, right?

Well, both of those things are true. But it doesn’t matter. Losing my dad was devastating. Is devastating. I wrote this in my journal back in July, and it’s still the most accurate description I can come up with:

It feels like one of the invisible forces of nature that keeps the earth spinning around its axis is disintegrating. I feel dizzy all the time, off balance, as if I might fall over at any point. Kind of like how flocks of birds suddenly start flying into stuff in the beginning of that terrible movie where the earth’s core stops spinning. Dad is a force that I don’t see often, but who helps to keep everything in its rightful place, and I’m not sure how to survive without it.

So if something feels a little strange to you today — if you almost trip, or you feel a small shock when you touch something, or you can’t get comfortable as you try to go to sleep — I think I know why. You are experiencing a disturbance in the force as a great man’s hold on this world starts loosening.

Losing my dad affected me more than I ever thought possible. I withdrew into my close relationships with family and friends for most of the year. I stopped writing. I threw myself into work and family, and shut everything else out. I just couldn’t do it. The fog of war is defined as follows:

The fog of war (German: Nebel des Krieges) is the uncertainty in situational awareness experienced by participants in military operations. The term seeks to capture the uncertainty regarding one’s own capability, adversary capability, and adversary intent during an engagement, operation, or campaign.

That’s basically how I felt all year. Uncertain about my own capabilities, cancer’s evil capabilities, and the adversarial intent of so many people online. I just couldn’t do it. I still can’t. But I feel like I have to start trying. So writing this is a first step towards an attempt to break free from my own personal fog of war.

The second thing I learned is how important funerals are. My favorite word I learned this year is liminality:

In anthropology, liminality (from the Latin word līmen, meaning “a threshold”) is the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of rituals, when participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they will hold when the ritual is complete. During a ritual’s liminal stage, participants “stand at the threshold” between their previous way of structuring their identity, time, or community, and a new way, which the ritual establishes.

This is applicable in so many situations, but it becomes especially true of funerals. During that week after my dad died, we were in liminality. He wasn’t with us any more, but we also weren’t living without him yet. We couldn’t. It’s too much to get used to, so we just stood at the threshold for a while. The planning, and of course the funeral itself, was our moment of liminality. We needed that ritual. It wasn’t just a way to honor my dad — although it was that too, of course. Above all, it was a way to force ourselves to look up and forward again.

The finale

I remember getting up on the Saturday after the funeral, having coffee with my mom, and asking each other, “Now what!?” It was a sad, empty feeling. But it was also the first time we were even able to ask the “Now what?” question. For the first time, we could start wondering how we do life without Dad. We weren’t healed, we weren’t over it, and frankly, I don’t think we ever will be. But we could at least start talking to each other about what “new normal” might look like. All thanks to the funeral, and a renewed appreciation for the importance of ritual.

So this year was a mess. For most of us. I enter 2017 with zero expectations, but I also enter it as a changed person. I am now living a life where I’m determined to honor Dad’s amazing legacy by treating every single person on earth with respect, and by always putting my family first. I enter 2017 cautiously optimistic, albeit with a permanent vacuum in my life.

Thank you, Dad, for everything. I miss you.